Trump bombs Venezuela, US abducts Maduro: All we know

Trump says the US will ‘run’ Venezuela for now while Maduro is brought to New York.

After months of threats and pressure tactics, the United States has bombed Venezuela and toppled its president, Nicolas Maduro, abducting him and his wife, Cilia Flores.

After being flown to the US on Saturday, Maduro and Flores were taken to a detention centre in New York, where he is being indicted on charges of “narcoterrorism” and conspiracy to import cocaine.

Venezuelan Vice President Delcy Rodriguez has slammed the “kidnapping” of Maduro, saying he is “the only president of Venezuela”, amid a global call for de-escalation.

US President Donald Trump says Washington will “run” Venezuela and tap its vast oil reserves, but he gave few details on how the US will do it.

The United Nations Security Council is due to meet on Monday on the matter as Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said the US actions set “a dangerous precedent”.

US media reports suggested Maduro could appear before a court as soon as Monday.

The attack on Venezuela and abduction of its socialist leader have few, if any, parallels in modern history. The US has previously captured foreign leaders, including Iraq’s Saddam Hussein and Panama’s Manuel Noriega.

Here is what we know about the US attacks and the lead-up to this escalation:

How did the attack unfold?

At a news conference on Saturday at his Mar-a-Lago resort in Palm Beach, Florida, Trump praised the operation to seize Maduro as one of the “most stunning, effective and powerful displays of American military might and competence in American history”.

The operation, named “Absolute Resolve”, was rehearsed for months, Trump administration officials said at the news conference.

Trump also told Fox News that US forces had practised their extraction of Maduro on a replica of the building where the operation took place. “They actually built a house which was identical to the one they went into with all the same, all that steel all over the place,” Trump said.

At 10:46pm on Friday (03:46 GMT on Saturday), Trump gave the green light.

On Friday night, “the weather broke just enough, clearing a path that only the most skilled aviators in the world could move through,” said General Dan Caine, chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff. He said about 150 aircraft were involved in the operation and they took off from 20 airbases across the Western Hemisphere.

As part of the operation, US forces disabled Venezuela’s air defence systems, and Trump said the “lights of Caracas were largely turned off due to a certain expertise that we have”, without elaborating.

Several explosions rang out across the Venezuelan capital, which US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth described as part of a “massive joint military and law enforcement raid” that lasted less than 30 minutes.

US helicopters then touched down at Maduro’s compound in Caracas at 2:01am (06:01 GMT) on Saturday, and the president and first lady were then taken into custody.

At 4:29am (08:29 GMT), Maduro was put on board a US aircraft carrier. An image that Trump posted on his Truth Social account appeared to show Maduro in a grey tracksuit with a black band covering his eyes and a water bottle in his hand on board the USS Iwo Jima.

After departing the Iwo Jima, US forces escorted Maduro on a flight that touched down at New York’s Stewart Air National Guard Base about 4:30pm (21:30 GMT).

What did Trump say?

In a Truth Social post a little after 09:00 GMT, Trump said the US had “successfully carried out a large scale strike against Venezuela and its leader, President Nicolas Maduro, who has been, along with his wife, captured and flown out of the Country”.

During his news conference on Saturday, Trump announced the US would “run” the country until a new leader is chosen.

“We’re going to make sure that country is run properly. We’re not doing this in vain,” he said. “This is a very dangerous attack. This is an attack that could have gone very, very badly.”

The president did not rule out deploying US troops in Venezuela and said he was “not afraid of boots on the ground if we have to”.

Trump also, somewhat surprisingly, ruled out working with opposition figure and Nobel Peace Prize winner Maria Corina Machado, who had dedicated her prize, which he wanted to win himself, to the US president.

“She doesn’t have the support within or the respect within the country,” he said.

The Constitutional Chamber of Venezuela’s Supreme Court ordered Rodriguez to serve as acting president after the US abduction of Maduro.

Where did the US attack Venezuela?

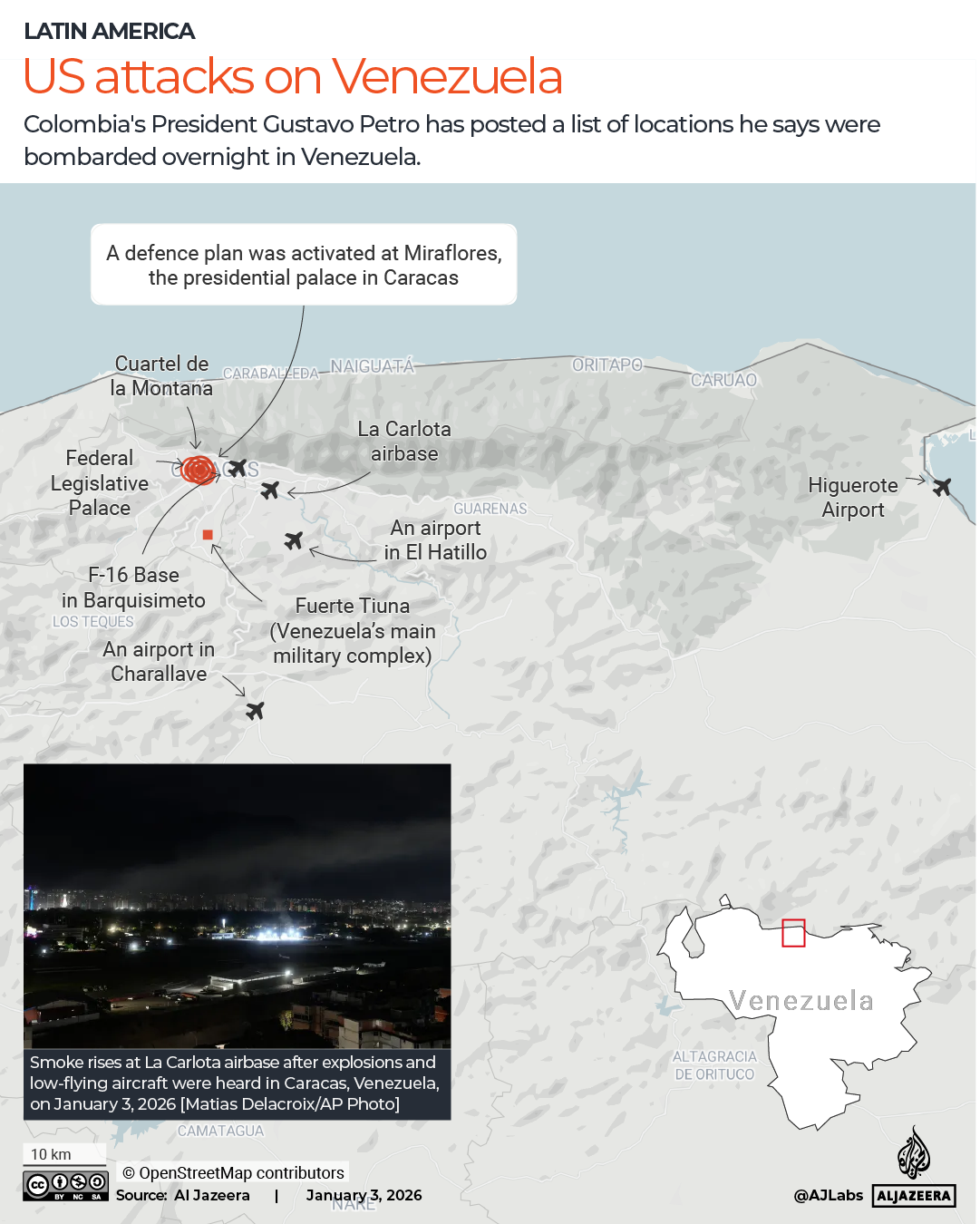

Venezuela’s government said the US struck Caracas and three states. While neither the US nor Venezuelan authorities have pinpointed the locations, Colombian President Gustavo Petro released a list of places he said had been hit.

They include:

- La Carlota airbase in Caracas, which was disabled

- Cuartel de la Montana in Caracas, the burial site of former President Hugo Chavez

- The Federal Legislative Palace in Caracas

- Fuerte Tiuna, Venezuela’s main military complex

- An airport in El Hatillo

- F-16 Base No 3 in Barquisimeto

- A private airport in Charallave near Caracas that was disabled

- Miraflores, the presidential palace in Caracas

- Central Caracas

- A military helicopter base in Higuerote that was disabled

Large parts of Caracas – including Santa Monica, Fuerte Tiuna, Los Teques, 23 de Enero and the southern areas of the capital – were left without electricity.

What led to these US attacks on Venezuela?

Trump in recent months has accused Maduro of driving narcotics smuggling into the US and has claimed the Venezuelan president is behind the Tren de Aragua gang that Washington has proscribed as a “foreign terrorist organisation”.

But Trump’s own intelligence agencies have said there is no evidence that Maduro is linked to Tren de Aragua, and US data show that Venezuela is not a major source of contraband narcotics entering the US.

Starting in September, the US military launched a series of strikes in the Caribbean Sea and eastern Pacific on boats that it claimed were carrying narcotics. More than 100 people have been killed in at least 30 such boat bombings, but the Trump administration has yet to present any public evidence that there were drugs on board, that the vessels were travelling to the US or that the people on the boats belonged to banned organisations as the US has claimed.

Meanwhile, the US began its largest military deployment in the Caribbean in at least several decades, spearheaded by the USS Gerald Ford, the world’s largest aircraft carrier.

In December, the US seized two ships carrying Venezuelan oil and has since imposed sanctions on multiple companies and their tankers, accusing them of trying to circumvent stringent American sanctions against Venezuela’s oil industry.

Then last week, the US struck what Trump described as a “dock” in Venezuela where he claimed drugs were being loaded onto boats.

Could all this be about oil?

Trump has so far framed his pressure and military action against Venezuela and in the Caribbean and Pacific as driven by a desire to stop the flow of dangerous drugs into the US.

But he has increasingly also sought Maduro’s departure from power despite a phone call in early December that the Venezuelan president described as “cordial”.

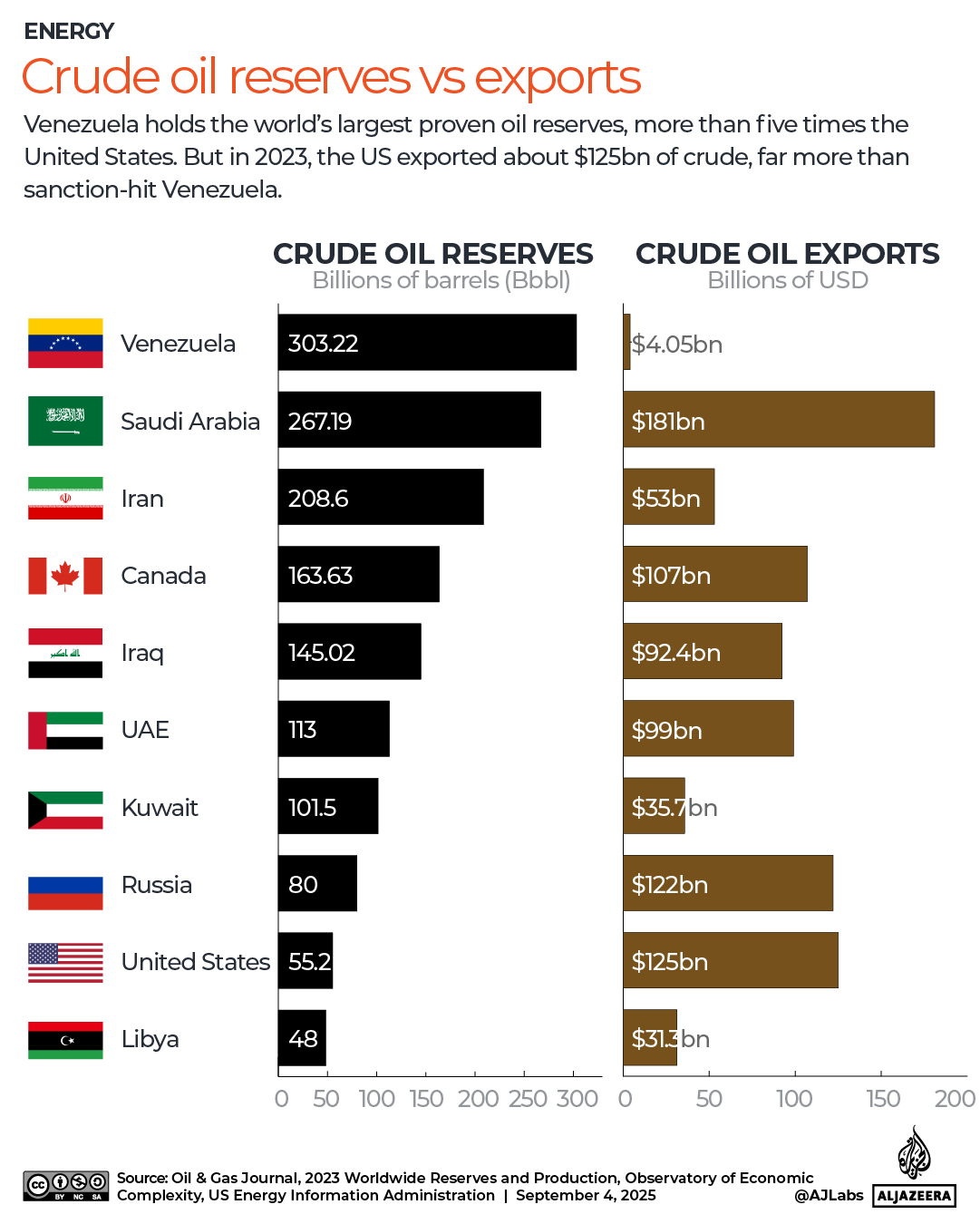

At the news conference on Saturday at Mar-a-Lago, Trump spoke about Venezuela’s oil. Its vast reserves of crude, unmatched in the world, amounted to an estimated 303 billion barrels as of 2023.

“We’re going to have our very large American oil companies go in and spend billions of dollars and fix the badly broken oil infrastructure” in Venezuela, Trump said.

He added: “We will make the great people of Venezuela very rich, independent and safe.”

In recent weeks, some senior aides of the US president have been even more open about Venezuela’s oil. On December 17, Deputy White House Chief of Staff Stephen Miller claimed the US had “created the oil industry in Venezuela” and the South American country’s oil, therefore, should belong to the US.

Although US companies were the earliest to drill for oil in Venezuela in the early 1900s, international law is clear: Sovereign states – in this case Venezuela – own the natural resources within their territories under permanent sovereignty over natural resources, established in international court rulings and a 1962 UN General Assembly resolution.

Venezuela nationalised its oil industry in 1976. Since 1999 when Chavez, Maduro’s mentor and predecessor, came to power, Venezuela has been locked in a tense relationship with the US.

Still, one major US oil company, Chevron, continues to operate in the country.

The Venezuelan opposition, led by Machado, had publicly called for the US to intervene against Maduro and has pointed to the oil reserves that US firms could tap more easily with a new government in power in Caracas.

Oil has long been Venezuela’s biggest export, but US sanctions since 2008 have crippled formal sales, and the country today earns only a fraction of what it once did.

How has Venezuela’s government reacted?

Trump noted that Rodriguez has been sworn in as Venezuela’s interim president.

After Maduro’s abduction on Saturday, his vice president demanded the US government provide proof of life for Maduro and Flores, and minced no words in denouncing the US actions.

“We call on the peoples of the great homeland to remain united because what was done to Venezuela can be done to anyone. That brutal use of force to bend the will of the people can be carried out against any country,” Rodriguez said in an address broadcast by the state television channel VTV.

How have other South American countries responded?

Analysts said they are split along ideological lines with right-wing governments applauding the removal of Maduro and left-wing governments criticising the move as illegal.

Colombia’s left-wing president posted on X: “The Colombian government rejects the aggression against the sovereignty of Venezuela and Latin America.” Petro called for an immediate meeting of the UN Security Council, of which Colombia is a member.

In Brazil, President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, who like Maduro was a union leader, said in a statement: “The bombings on Venezuela’s territory and the capture of its president cross an unacceptable line.”

While Chile’s outgoing leftist president, Gabriel Boric, also condemned the US attack, far-right President-elect Jose Antonio Kast welcomed the news in a post on X: “Now begins a greater task. The governments of Latin America must ensure that the entire apparatus of the regime abandons power and is held accountable.”

Trump’s closest ally in the region is Argentinian President Javier Milei, who expressed approval of the Trump administration’s move via videos posted to X while the right-wing president of Ecuador, Daniel Noboa, wrote on X: “All the criminal narco-Chavistas will have their moment. Their structure will finally collapse across the continent.”

How have Venezuelans reacted so far?

On Saturday morning, the streets of Caracas were mostly quiet as security forces patrolled and people stayed indoors. Later in the day, however, supporters of Maduro’s government – some chanting, “We want Maduro” – began to gather in the capital to protest against his capture.

They were led in a march by Mayor Carmen Melendez, who wore a military uniform. She described the US action as a “kidnapping”.

Many members of the Venezuelan diaspora, however, have taken to the streets in other countries to celebrate Maduro’s removal.

Maduro presided over crackdowns on protests and the opposition, a debt default, hyperinflation and plummeting living standards. About 20 percent of the population of Venezuela – about 7.7 million people – have left the country since 2014, mostly to seek better economic opportunities elsewhere, according to data from the International Organization for Migration. About 85 percent have moved to neighbouring countries in Latin America and to the Caribbean.

“We are free,” Khaty Yanex, a Venezuelan woman who has lived in Chile for the past seven years, told the Reuters news agency. “We are all happy that the dictatorship has fallen and that we have a free country.”

Another Venezuelan celebrating in Chile, Jose Gregorio, said: “My joy is too big. After so many years, after so many struggles, after so much work, today is the day. Today is the day of freedom.”

In Spain, Venezuelan Agustin Rodriguez told a local television broadcaster that the US strikes “may be necessary to find a way out for the country in which there can be a return to power alternation, where there can be a future”, Reuters reported.

Andres Losada told Reuters he has lived for three years in Spain, where the Venezuelan diaspora numbers about 400,000 people. He said: “Although what people are going through in Caracas is tough, I believe that beyond that, there is a light that will lead us to freedom.”

What happens to Maduro next?

In a statement posted on X, US Attorney General Pam Bondi announced that Maduro and Flores have been indicted on federal charges in the Southern District of New York.

Maduro has been charged with “narco-terrorism conspiracy, cocaine importation conspiracy” among other charges, Bondi said. It was unclear if his wife is facing the same charges, but she referred to the Maduro couple as “alleged international narcotraffickers”.

“They will soon face the full wrath of American justice on American soil in American courts,” she said.

Mike Lee, a senator from Utah and a member of Trump’s Republican Party, posted on X that he had spoken to US Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who had told him Maduro had been “arrested by US personnel to stand trial on criminal charges in the United States, and that the kinetic action we saw tonight was deployed to protect and defend those executing the arrest warrant”.

In 2020 during Trump’s first presidential term, US prosecutors had charged Maduro with running a cocaine-trafficking network.

But US officials remained silent on the violations that Maduro’s capture and the attacks on Venezuela represent to the UN Charter’s principles of sovereignty and territorial integrity of nations.

Russia and Cuba, which are close Maduro allies, condemned the attacks. Colombia, a neighbour of Venezuela that has itself been in Trump’s crosshairs, said it “rejects the aggression against the sovereignty of Venezuela and of Latin America” even though Bogota itself does not recognise Maduro’s government.

Most other nations have been relatively muted in their response to the US aggression so far.

What’s next for Venezuela?

Senior leaders seen as close to Maduro and influential within the Venezuelan hierarchy include Interior Minister Diosdado Cabello; National Assembly President Jorge Rodriguez, who is the interim president’s brother; and Defence Minister Vladimir Padrino Lopez.

It is unclear whether the state apparatus that Chavez and Maduro built over a quarter-century will last without the two leaders.

“Maduro’s capture is a devastating moral blow for the political movement started by Hugo Chavez in 1999, which has devolved into a dictatorship since Nicolas Maduro took power,” Carlos Pina, a Venezuelan analyst based in Mexico, told Al Jazeera.

If the US does engineer – or has already engineered – a change in the government, the opposition’s Machado could be a front runner to take Venezuela’s top job although it is unclear how popular that might be. In a November poll in Venezuela, 55 percent of participants were opposed to military intervention in their country, and an equal number were opposed to economic sanctions against Venezuela.

In a post on X on Saturday, Machado said her opposition colleague Edmundo Gonzalez, who the US and other countries have recognised as the rightful winner of the 2024 election against Maduro, should now assume the presidency. She added that the opposition would restore order and free all political prisoners.

But Trump might be mistaken if he thinks the US can stay out of the chaos that is likely to follow in a post-Maduro Venezuela, said Christopher Sabatini, a senior research fellow for the Latin America, US and North America programme at Chatham House.

“Assuming even if there is regime change – of some sort, and it’s by no means clear even if it does happen that it will be democratic – the US’s military action will likely require sustained US engagement of some sort,” he said.

“Will the Trump White House have the stomach for that?”